|

|

The Film

Don’t Torture a Duckling (Lucio Fulci, 1972) Don’t Torture a Duckling (Lucio Fulci, 1972)

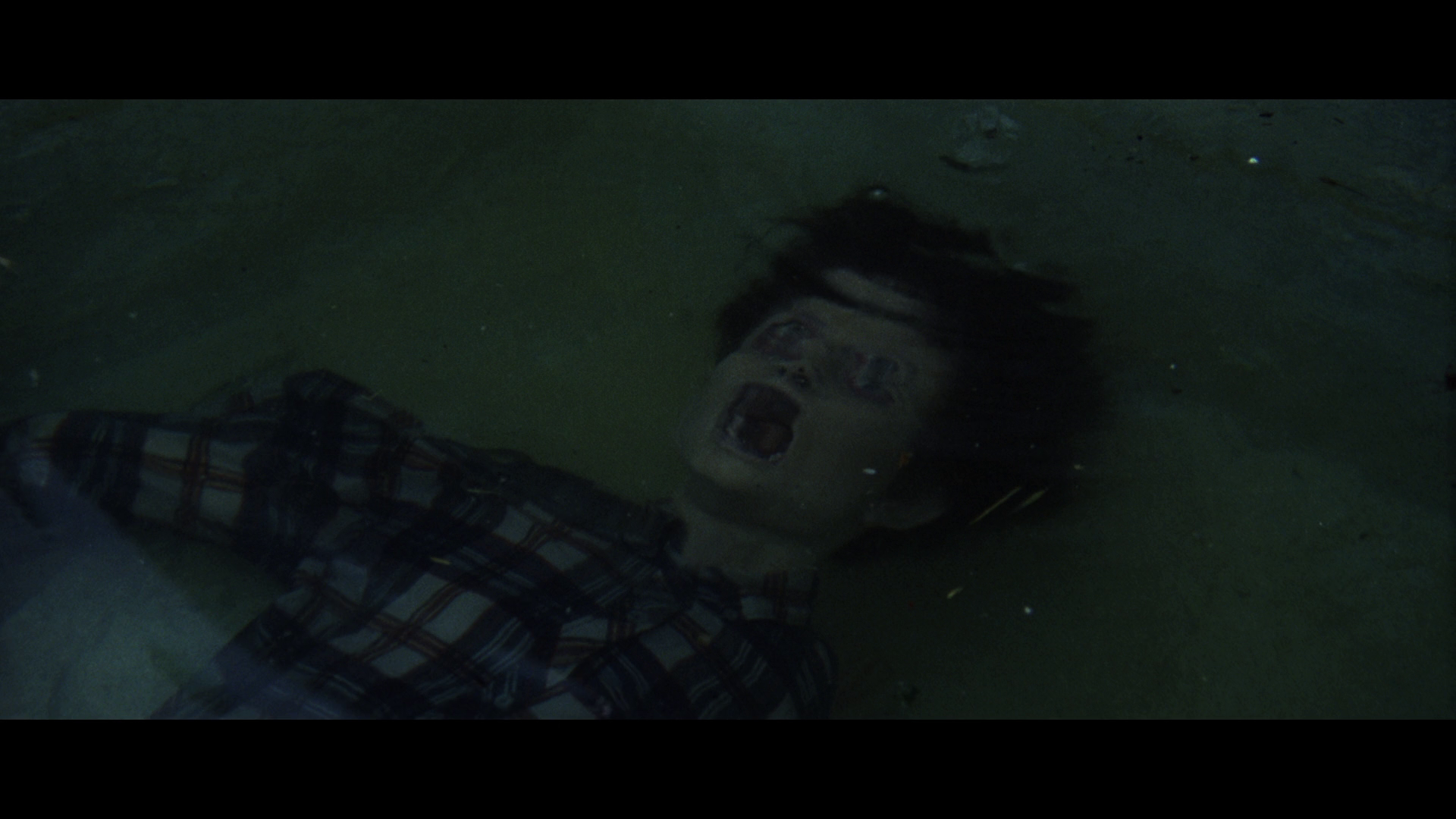

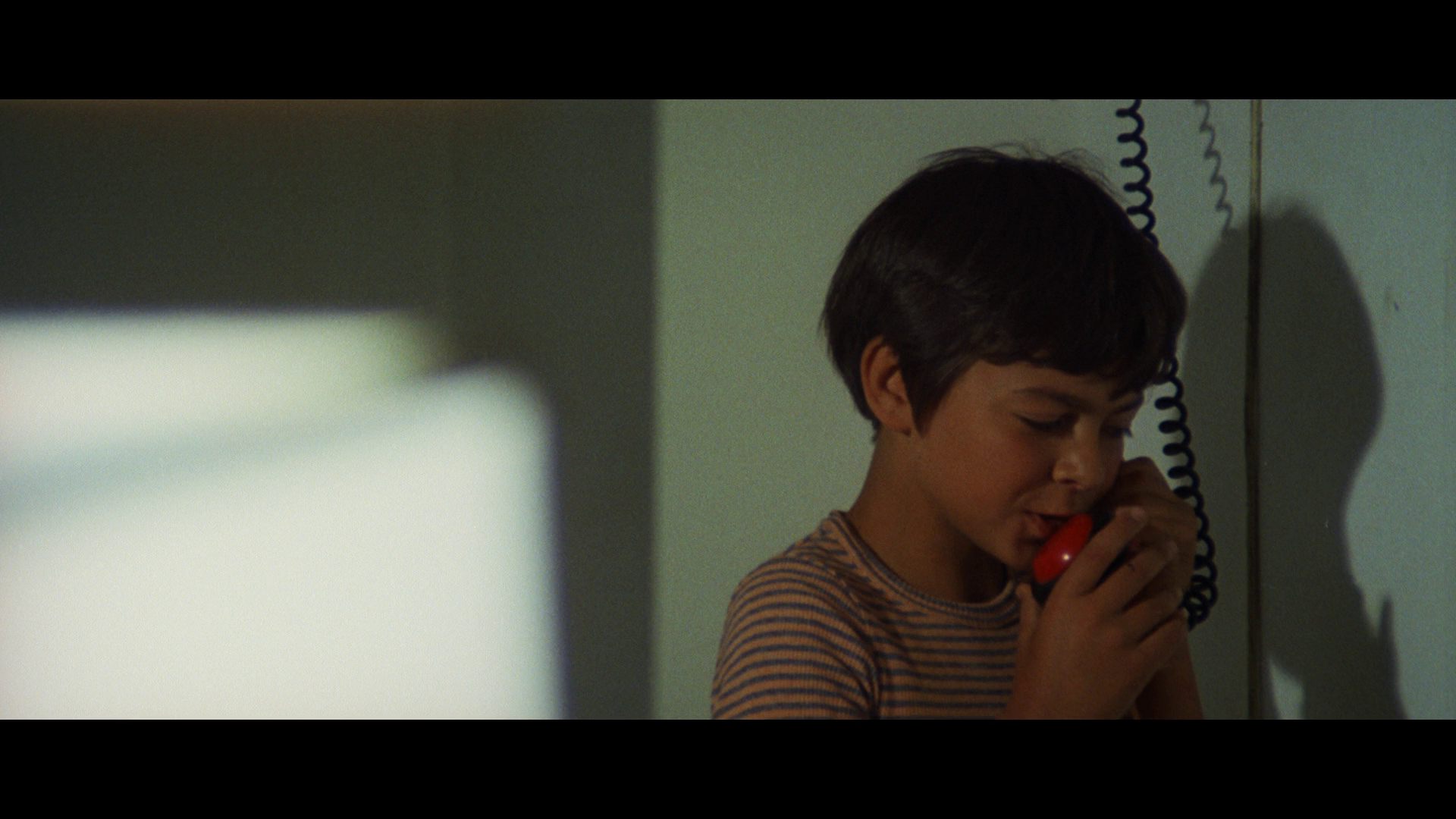

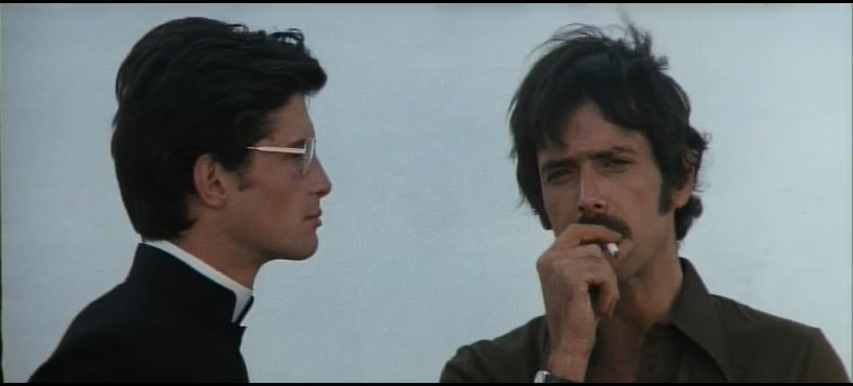

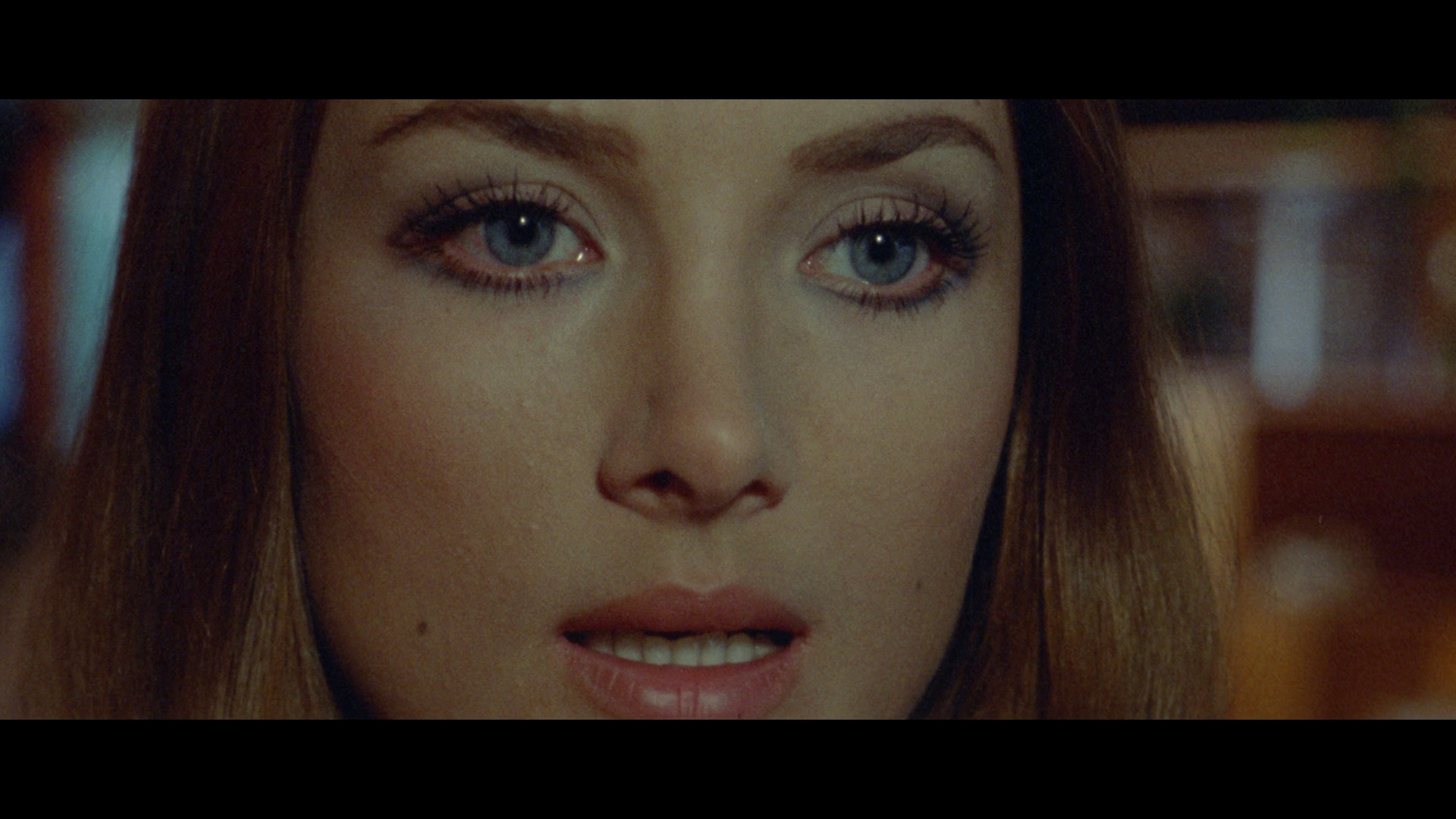

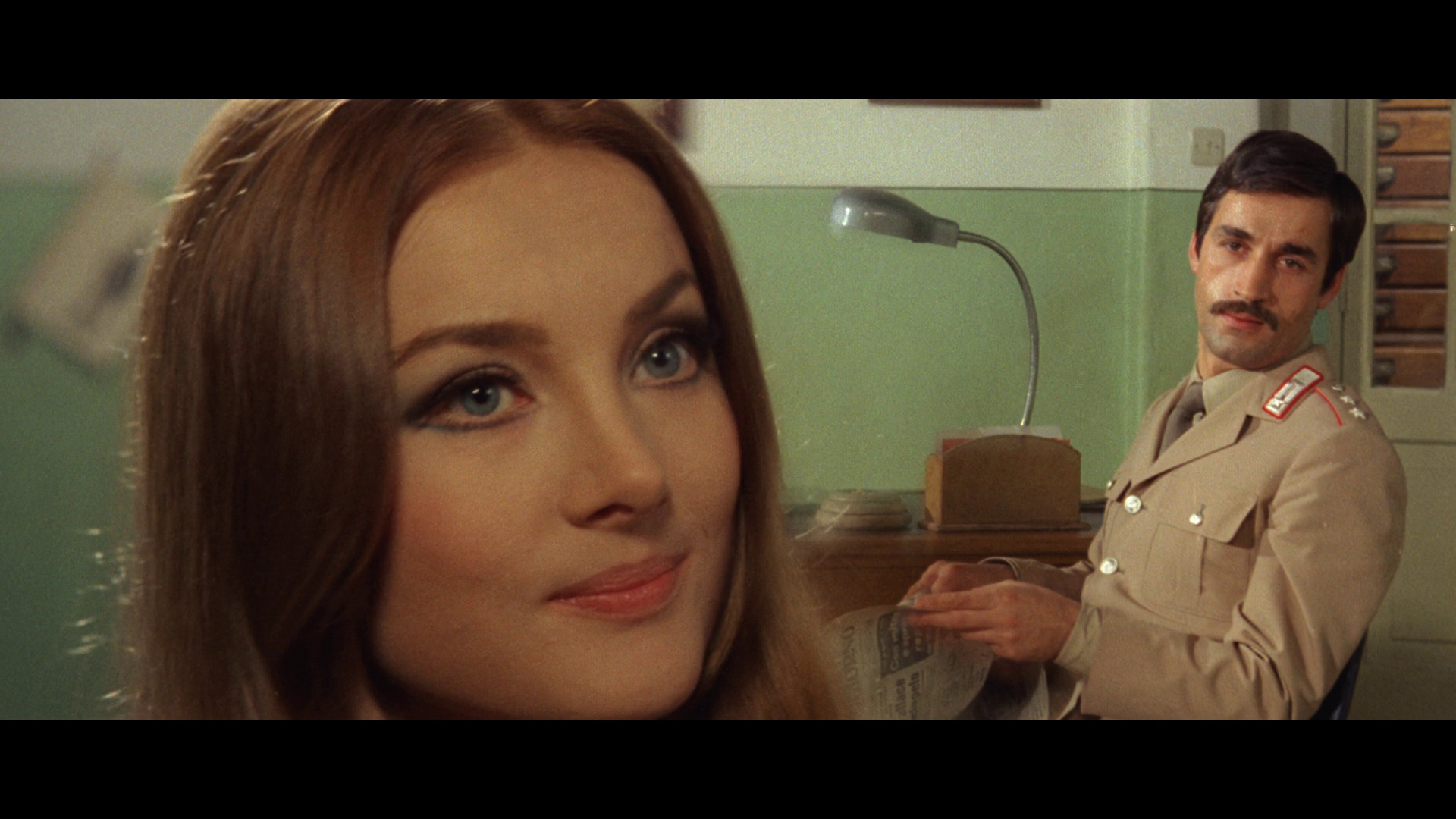

In an Apulian village, the local ‘witch’, Maciara (Florinda Bolkan), digs frantically with her hands, disinterring the skeletal remains of an infant. Later, a group of boys from the village spy on prostitutes from the city, who have met with their clients at the ‘haunted house’ – a derelict building in the countryside. Returning home, one of the boys, Michele Spriano, is teased by his mother’s employer Patrizia (Barbara Bouchet), a young woman from the city who has been sent by her father to live in his rural villa owing to her drug habit. Patrizia, who employs Michele’s mother as a housekeeper, allows Michele to see herself naked. Meanwhile, one of Michele’s friends, twelve year old Bruno Lo Cascio, disappears. Bruno’s father (Andrea Aureli) receives a telephone call demanding a ransom of six million lire in exchange for Bruno. Working with the police, who are aided by a detective from Milan, Bruno’s father drops off the ransom money at the location, a derelict factory, specified by the man claiming to be Bruno’s captor. Waiting at the location, the police arrest Barra (Vito Passeri), the village idiot. Barra, however, protests his innocence. The case is covered by Martelli (Tomas Milian), a journalist with The Milan Standard. Martelli believes strongly that Barra is indeed innocent of the crime; the police begin to doubt Barra’s involvement in the murder of Bruno too. When another boy is discovered drowned in a trough, the investigation continues. Martelli speaks with Father Alberto (Marc Porel), who arranges activities for the village’s children; Alberto casts suspicion upon Patrizia.  When Michele is found murdered, Patrizia seems a likely suspect. However, the police turn their attention towards the witch, Maciara. They speak with her mentor, a magician named Uncle Francesco (Georges Wilson) who, despite his reputed wealth, lives a hermit’s life in a jerry-rigged stone building in the countryside. In a cave, the police discover the infant’s skeleton and learn that the child was Maciara’s. Legend has it that the child was conceived when Maciara was involved in an exorcism of sorts, and therefore the baby was claimed to be ‘the Devil’s son’; but as the local policeman tells the Milanese detective, this is also a label applied by the locals to children who have any sort of deformity. When Michele is found murdered, Patrizia seems a likely suspect. However, the police turn their attention towards the witch, Maciara. They speak with her mentor, a magician named Uncle Francesco (Georges Wilson) who, despite his reputed wealth, lives a hermit’s life in a jerry-rigged stone building in the countryside. In a cave, the police discover the infant’s skeleton and learn that the child was Maciara’s. Legend has it that the child was conceived when Maciara was involved in an exorcism of sorts, and therefore the baby was claimed to be ‘the Devil’s son’; but as the local policeman tells the Milanese detective, this is also a label applied by the locals to children who have any sort of deformity.

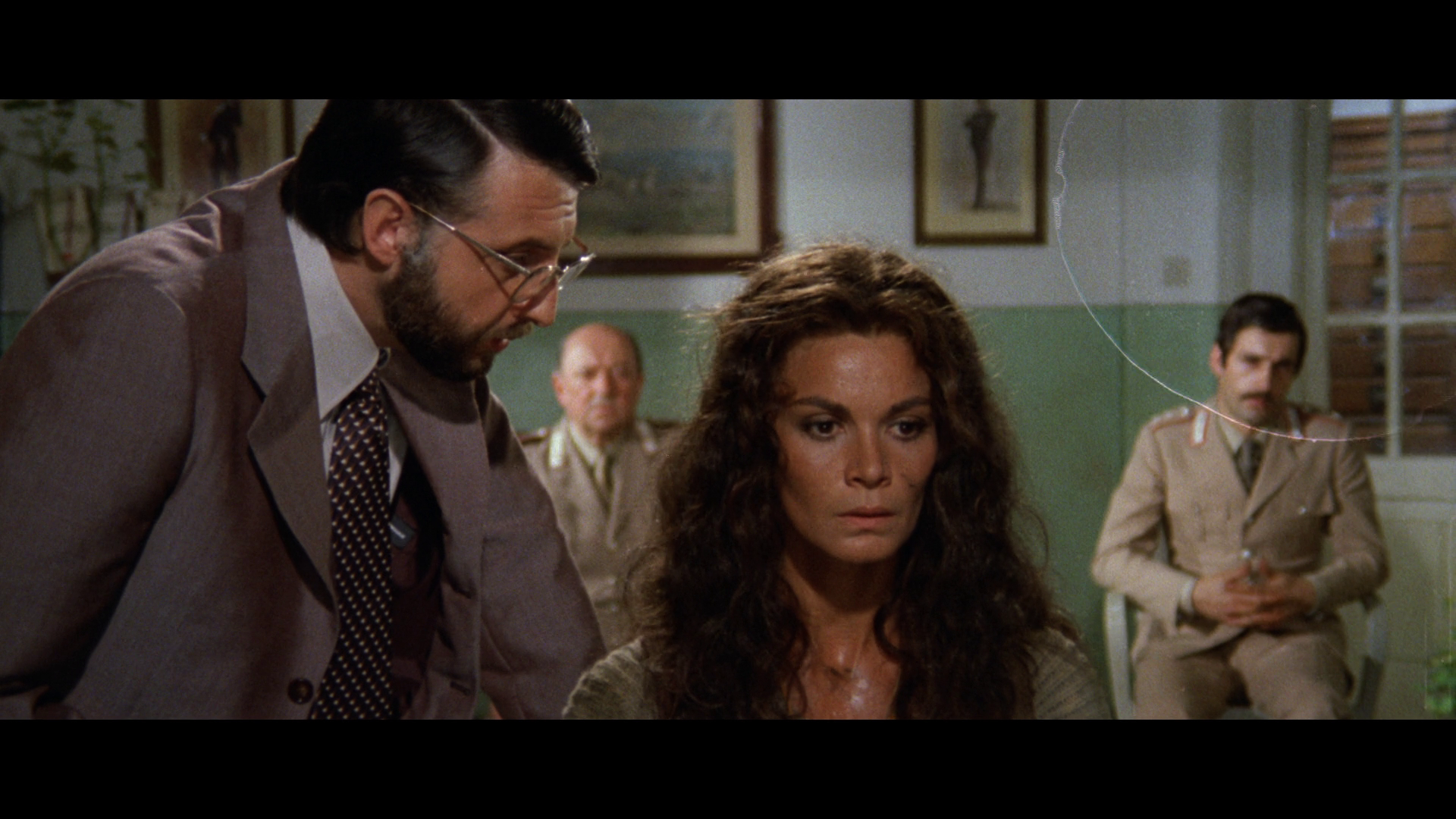

The police capture and arrest Maciara. Under interview, she reveals that she believes herself to be guilty of killing the boys; however, she also reveals that she believes the boys to have died as a result of a spell she cast, involving tar dolls, after she saw the boys playing near the grave of her baby. The police realise that Maciara is guilty of nothing more than superstition, and they set her free. In the film’s most harrowing sequence, Maciara finds herself in a cemetery where she is set upon by a group of local men, who whip her with chains. Maciara manages to crawl to the edge of the new highway that runs past the village, where the passers-by notice her but refuse to offer assistance. There, she dies. The death of the witch doesn’t stop the murders: another boy, Mario, is discovered dead. Patrizia is suspected by the police, but she and Martelli team up to uncover the real killer.  The thrilling all’italiana (or giallo all’italiana/Italian-style thriller) has always been a nebulous beast, running the gamut from erotic melodramas and political thrillers to more outré supernatural thrillers. English-speaking fans of Italian-style thrillers tend to use the label giallo to identify such films, whereas to Italian audiences a giallo is of course a thriller of any type, regardless of its country of origin. Like film noir, the thrilling/giallo all’italiana h often (but not always) feature recurring visual elements, in narrative structure and thematic concerns the films are actually incredibly diverse. In terms of narrative ‘types’, the thrilling all’italiana encompasses paranoid political thrillers (La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films). The thrilling all’italiana (or giallo all’italiana/Italian-style thriller) has always been a nebulous beast, running the gamut from erotic melodramas and political thrillers to more outré supernatural thrillers. English-speaking fans of Italian-style thrillers tend to use the label giallo to identify such films, whereas to Italian audiences a giallo is of course a thriller of any type, regardless of its country of origin. Like film noir, the thrilling/giallo all’italiana h often (but not always) feature recurring visual elements, in narrative structure and thematic concerns the films are actually incredibly diverse. In terms of narrative ‘types’, the thrilling all’italiana encompasses paranoid political thrillers (La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films).

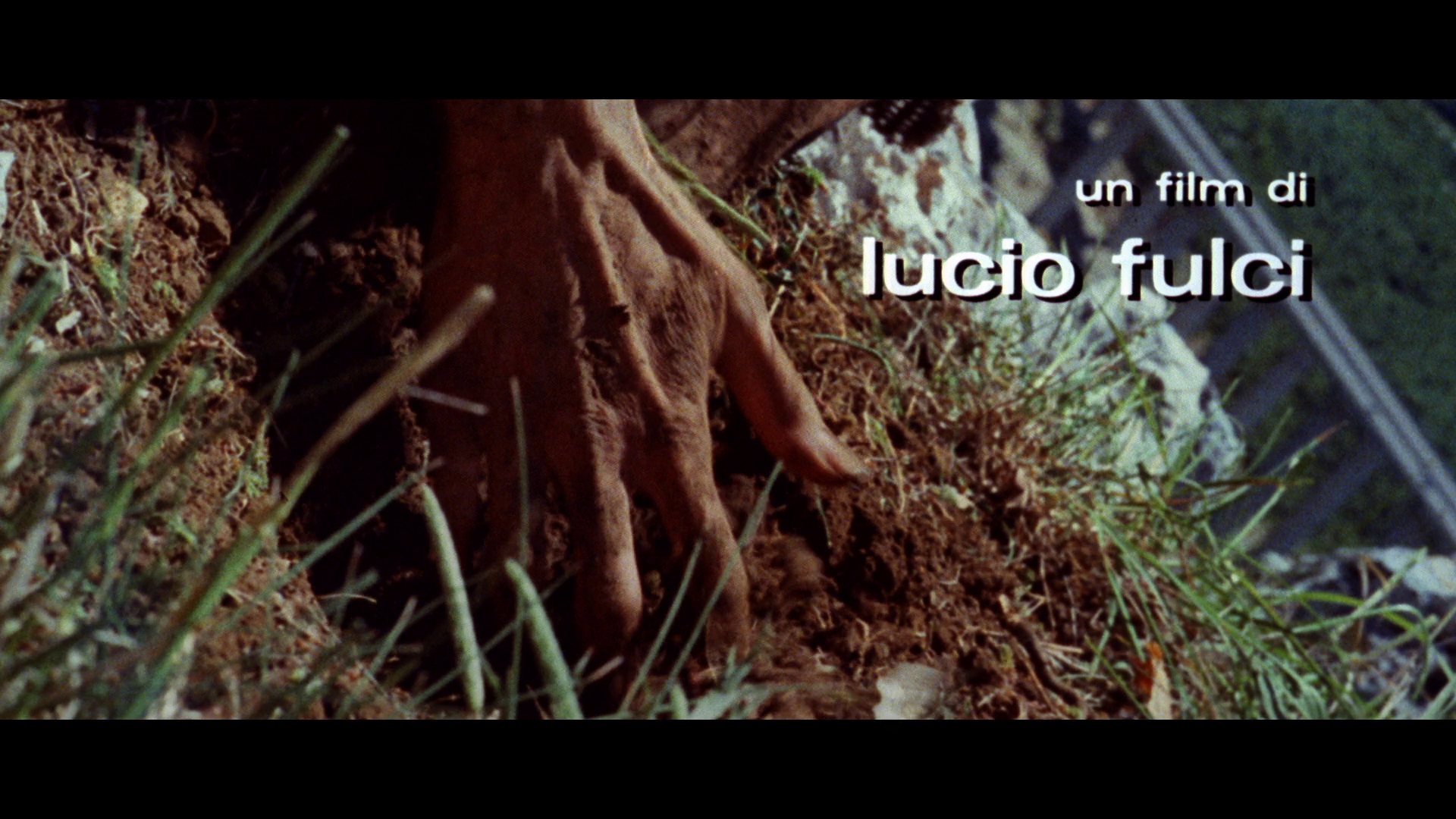

Lucio Fulci’s Non si sevizia un paperino (Don’t Torture a Duckling, 1972) is an incredible example of the thrilling all’italiana, a psychosexual thriller with a rural setting (which therefore has some superficial similarities with The House with Laughing Windows). Some urban gialli all’italiana featured notable excursions by their protagonists into the rural space: for example, Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) journey to the countryside to speak with the cat-eating artist Berto Consalvi (Mario Adorf) in Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970). However, Don’t Torture a Duckling is set entirely within a rural community.  The opening shots of the film play on the juxtaposition of the motorway, a symbol of progress, with the superstitious beliefs of the rural community. The film opens with long shots of the motorway which connects the countryside with the cities, the camera panning from this (with the help of a concealed edit) to a tight close-up of the witch’s hands frantically clawing at the dirt and unearthing the skeletal body of her infant son. The sequence offers a wordless depiction of the countryside as ‘sinister’, thanks to the enigmatic nature of the imagery (the scene is followed by another, set in the village church, in which one of the boys holds his hands in front of his face and looks through the gaps in his fingers) and Riz Ortolani’s haunting music. Throughout the rest of the film, this juxtaposition of the urban with the rural – and the connotations that ensue – becomes increasingly important. The local police chief, tolerant of the witch and vocal in his assertions of what he believes to be her innocence, is contrasted with the Milanese detective who arrives in the community to investigate the case; Patrizia, the woman from Milan who has been sent by her father to live in his modern villa on the outskirts of the village, is represented as a figure of suspicion owing to the manner in which she is surrounded by trappings of cosmopolitanism (a flash car and short skirts, which speak of her ‘liberated’ sexuality). Progress is set against repression; the urban is contrasted with the rural, and it seems that these opposites may be impossible to reconcile. However, this isn’t a didactic treatise: Fulci treats both sets of paradigms with equal cynicism. The opening shots of the film play on the juxtaposition of the motorway, a symbol of progress, with the superstitious beliefs of the rural community. The film opens with long shots of the motorway which connects the countryside with the cities, the camera panning from this (with the help of a concealed edit) to a tight close-up of the witch’s hands frantically clawing at the dirt and unearthing the skeletal body of her infant son. The sequence offers a wordless depiction of the countryside as ‘sinister’, thanks to the enigmatic nature of the imagery (the scene is followed by another, set in the village church, in which one of the boys holds his hands in front of his face and looks through the gaps in his fingers) and Riz Ortolani’s haunting music. Throughout the rest of the film, this juxtaposition of the urban with the rural – and the connotations that ensue – becomes increasingly important. The local police chief, tolerant of the witch and vocal in his assertions of what he believes to be her innocence, is contrasted with the Milanese detective who arrives in the community to investigate the case; Patrizia, the woman from Milan who has been sent by her father to live in his modern villa on the outskirts of the village, is represented as a figure of suspicion owing to the manner in which she is surrounded by trappings of cosmopolitanism (a flash car and short skirts, which speak of her ‘liberated’ sexuality). Progress is set against repression; the urban is contrasted with the rural, and it seems that these opposites may be impossible to reconcile. However, this isn’t a didactic treatise: Fulci treats both sets of paradigms with equal cynicism.

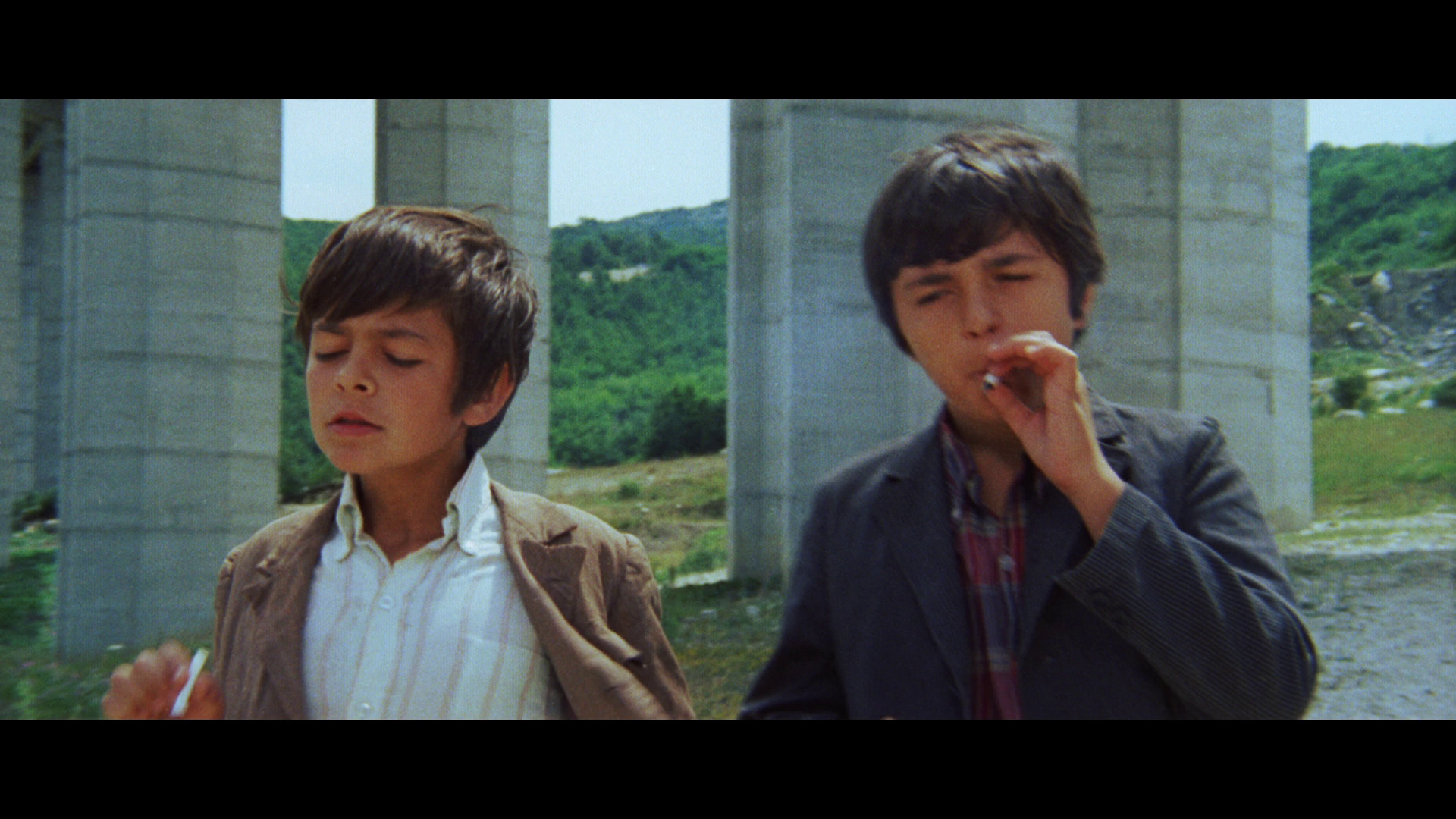

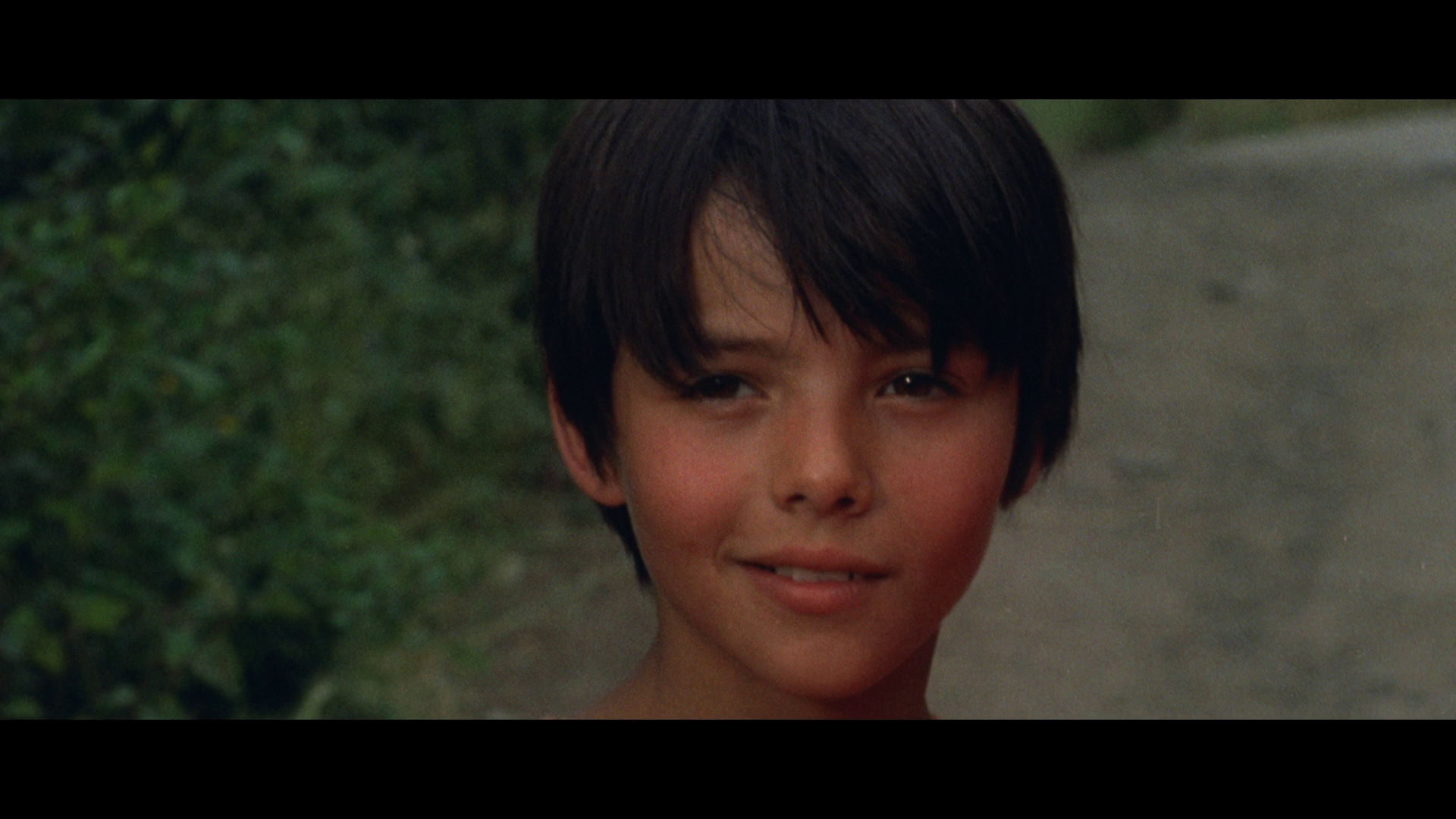

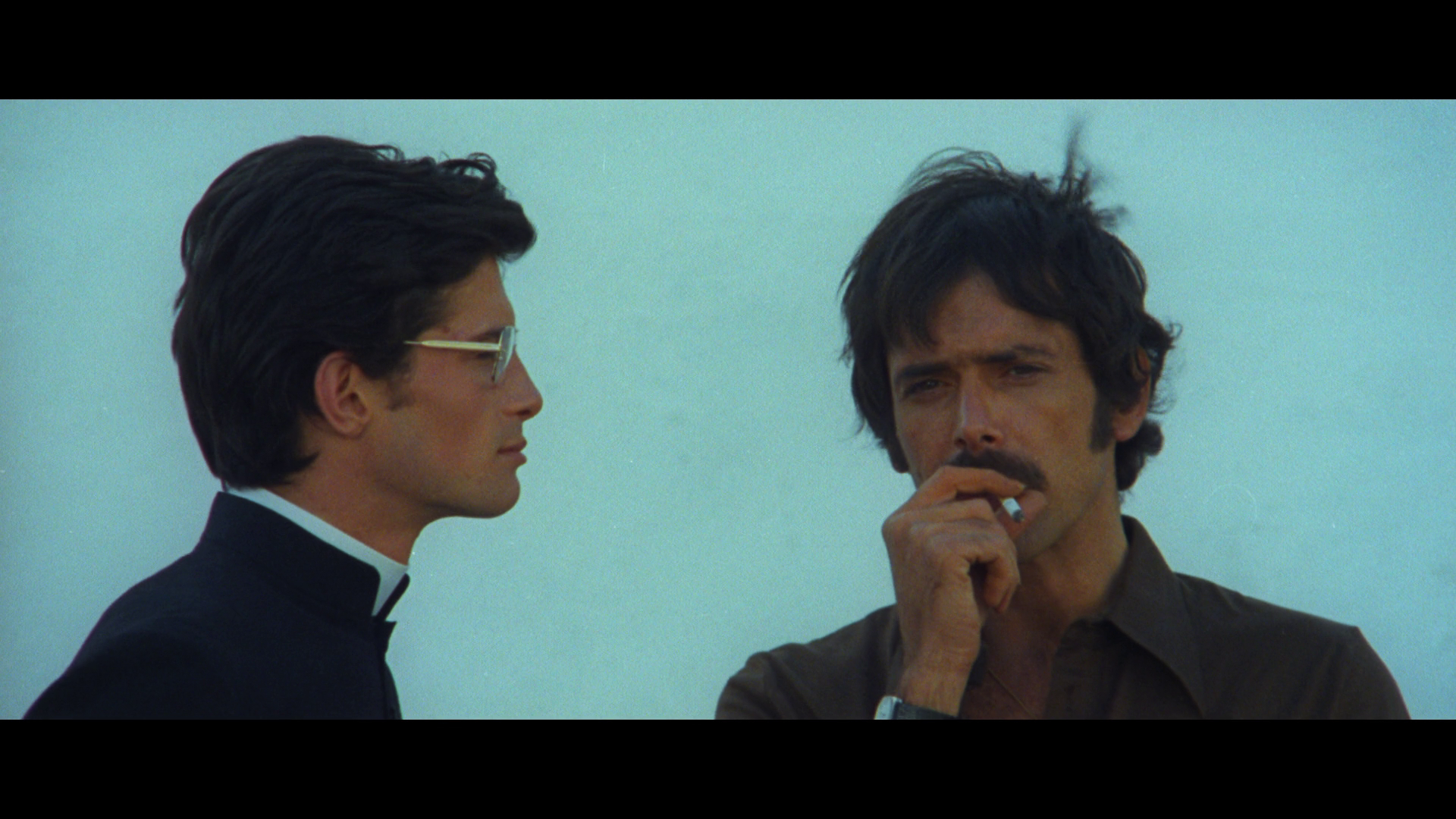

Don’t Torture a Duckling is one of a number of gialli all’italiana that, alongside Aldo Lado’s Chi l’ha a vista morire? (Who Saw Her Die?, 1972), The House with Laughing Windows, Umberto Lenzi’s Sette orchidee macchiate di rosso (Seven Bloodstained Orchids, 1972) and Antonio Bido’s Solamente nero (Bloodstained Shadow, 1978), could be labelled ‘anti-clerical’ for its association of priesthood with deviance. The priest claims to be defending against sin, and this is his primary motivation for committing the crimes for which he is responsible. He is an agent of repression, attempting to protect the boys from corruption by the modern world. (‘[N]obody understands it’s our tolerance to blame’ for the moral decline of modern society, Father Alberto suggests to Martelli, ‘What’s a poor priest to do?’) However, his is just one of a number of peccadilloes that are exposed as the narrative progresses. As Danny Shipka has noted, ‘[l]ike Bava, [Fulci] populates [the film] with people who have deep neuroses’ (Shipka, 2011: 90). Amongst this group are the ‘village idiot’; the witch who claims to have killed the boys via the use of magic; and Patrizia, a recovering/lapsed drug addict who finds humour in sexually teasing the village’s young boys. Amidst this, the boys’ lapses into voyeurism, visiting the ‘haunted house’ (a derelict, isolated house on the outskirts of the community) where they watch the prostitutes from the city in their liaisons with their ‘johns’, seems comparatively innocent and naïve.  The children themselves are introduced smoking and mimicking the behaviour of adults – developing a nascent interest in sex and sexuality which leads them to spy on the activities of the prostitutes and their clients. Patrizia recognises Michele’s dawning sexuality and exploits it, allowing the boy to see her in the nude and teasing him (‘Go on. Look at me […] Is it the first time you’ve seen a woman naked? Tell me, how many girls have you slept with? [….] Would you like to do it with me?’). Later, she subtly mocks another of Michele’s compatriots, asking him if he would change the tyre on her car in exchange for a kiss. Patrizia’s aberrant sexuality is connected to her association with the city (a place of libertarianism, it seems) and her status as a drug addict. That, like Chi l’ha a vista morire?, the killer chooses children as his victims is symbolic: as Karola has noted in relation to Mario Bava’s use of cruel and cursed children in his films, within the context of Italian cinema such a representation of childhood may be read symbolically, given that Italian neo-realist films frequently used children as symbols of Italy’s future (Karola, 2003: 228). This is reinforced when Bruno’s body is discovered by the police, the boy’s corpse unearthed in a shallow grave; a very brief cut to a shot of Bruno, alive and smiling, is inserted into this event – an analeptic fragment which represents Bruno’s parents’ memories of their son. This brief shot is followed by an outpouring of grief and anger directed towards Barra, the presumed culprit. The children themselves are introduced smoking and mimicking the behaviour of adults – developing a nascent interest in sex and sexuality which leads them to spy on the activities of the prostitutes and their clients. Patrizia recognises Michele’s dawning sexuality and exploits it, allowing the boy to see her in the nude and teasing him (‘Go on. Look at me […] Is it the first time you’ve seen a woman naked? Tell me, how many girls have you slept with? [….] Would you like to do it with me?’). Later, she subtly mocks another of Michele’s compatriots, asking him if he would change the tyre on her car in exchange for a kiss. Patrizia’s aberrant sexuality is connected to her association with the city (a place of libertarianism, it seems) and her status as a drug addict. That, like Chi l’ha a vista morire?, the killer chooses children as his victims is symbolic: as Karola has noted in relation to Mario Bava’s use of cruel and cursed children in his films, within the context of Italian cinema such a representation of childhood may be read symbolically, given that Italian neo-realist films frequently used children as symbols of Italy’s future (Karola, 2003: 228). This is reinforced when Bruno’s body is discovered by the police, the boy’s corpse unearthed in a shallow grave; a very brief cut to a shot of Bruno, alive and smiling, is inserted into this event – an analeptic fragment which represents Bruno’s parents’ memories of their son. This brief shot is followed by an outpouring of grief and anger directed towards Barra, the presumed culprit.

The witch, whose actions are the least harmless, becomes marked as a victim largely by her association with the supernatural and her status as an outsider figure. When she is caught by the police, she confesses to the murders of the boys – but believes she has committed these murders via the use of magic. The police recognise this claim as utter nonsense and release the witch, but she is soon lynched by locals who are more receptive to her claim; in a cemetery, a group of men whip the witch with chains, the weapons biting into her flesh and tearing chunks of it off in a sequence which is intense and graphic. It’s a striking sequence, diegetic pop music playing on a radio in counterpoint to the hideousness of the onscreen action; the effects carry the violence nicely (unlike the rather more shonky visual effects at the film’s climax). The emphasis on the prolonged chainwhipping and the graphic visual effects recall Fulci’s later pictures – and particularly, the chainwhipping of the warlock Schweik during the precredits sequence of L’aldila (The Beyond, 1981). With this sequence, Fulci also pulls of a moment of narrative daring comparable to the pivotal murder of Marion Crane in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960): until this point in the picture, the witch has been one of the, if not the most, likely suspects in the murders of the young boys; however, during her interrogation by the police she reveals herself to be a pitiable creature, believing that her use of magic has caused the deaths of the children. In the chainwhipping scene, where previously we have been allied with the villagers in seeing the witch’s behaviour as sinister, our sympathies are reversed: we see the witch as pathetic and worthy of our emotional investment, her brutal murder committed by the equally superstitious villagers. The witch manages to crawl towards the motorway, expiring by the side of the road as drivers deliberately ignore her plight; she becomes a victim of modernity, the city detective commenting that this is ‘A horrifying crime […] It makes us ashamed of ourselves. Is this it? We can build highways but we can’t overcome ignorance and superstition?’

Video

The film takes up 26Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 105:06, with an intermission at the halfway point and some post-credits music which plays out over a black screen. The film takes up 26Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 105:06, with an intermission at the halfway point and some post-credits music which plays out over a black screen.

Don’t Torture a Duckling was photographed in Techniscope and is here presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. As with other Techniscope pictures, the film was made using spherical lenses. Techniscope and similar 2-perf widescreen processes were cost-saving in the sense that they enabled the production of a widescreen image without the use of expensive anamorphic lenses, and by reducing the size of each frame by half (from 4-perforations to 2-perforations) halved the negative costs involved in making a film. (However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by more expensive lab costs, which for Techniscope productions steadily increased throughout the 1970s; this is sometimes cited as one of the reasons why Techniscope became less popular during the late 1970s and early 1980s.) Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)

This presentation of Don’t Torture a Duckling has the hallmarks of a dye transfer presentation of a Techniscope picture, with deep and rich blacks (especially in comparison with the old DVD presentations of the same picture – some visual comparisons with the Anchor Bay DVD released nearly 20 years ago are included at the bottom of this review) and a grain structure that is denser than a film shot using an anamorphic widescreen process but not as aggressive as Techniscope prints made using the dupe negative process. The HD presentation displays an incredibly noticeable step-up in terms of detail, in comparison with the film’s DVD releases; contrast levels are much improved too, with richly defined midtones and even, balanced highlights. Much of the film is shot in harsh Mediterranean sunlight, with strong shadows tapering off into rich blacks. Colours are rich, naturalistic and consistent – the lush greens of the countryside in the film’s opening sequence, and the naturalistic blue of the sky. Reds sometimes look a little ‘hot’, but this could be owing to the shooting conditions. The image has a strong sense of depth throughout (depth being a characteristic of the film’s photography, thanks to the 2-perf format, but also via the employment of split-dioptre lenses during a number of scenes). The encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. There is little damage present, but some frames exhibit white scratches and flecks (see the large frame grab below).

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with the option of watching the film (i) in Italian with optional English subtitles, or (ii) in English with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. Both audio options are LPCM 1.0. Selecting option (i) also plays the film with all text inserts and credits in Italian, again accompanied by subtitles; selection option (ii) plays the film with text inserts and credits in English. Audio options can’t be changed ‘on the fly’: the viewer must return to the disc menu in order to switch from Italian to English (or vice versa). The English dub for this picture is acceptable but nothing special. The Italian version works much better, especially in juxtaposing the slang and accents of metropolitan Italy with those of the rural community. (This aspect will, however, be lost on non-Italian speaking audiences, regardless of which audio track is selected.) Both tracks are rich, problem-free and demonstrate good range. Subtitles in both cases are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

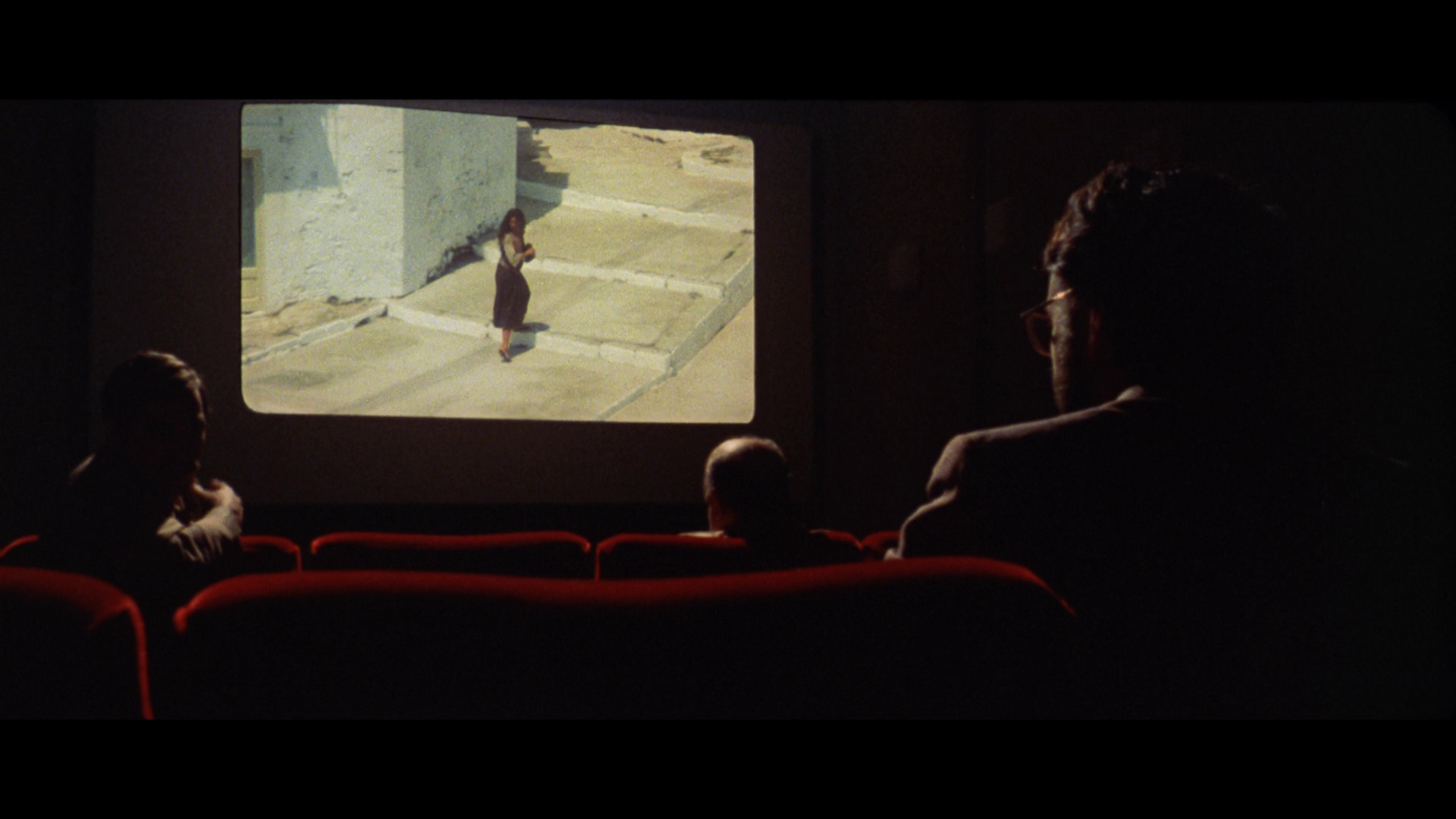

- An audio commentary by Troy Howarth. Howarth freely admits that Don’t Torture a Duckling is one of his favourite films, and this commentary track is riddled with enthusiasm for the picture. He discusses the film’s bleak tone and its relationship with other contemporaneous examples of the giallo all’italiana. It’s a breathless and thorough commentary track which engages with the film on an aesthetic and thematic level. - ‘Giallo a la campagna’ (27:44). Mikel J Koven talks about the exhibition contexts for gialli all’italiana in Italy during the 1970s and cinema culture in that era. Koven reflects on some of the stronger imagery in the film, intended, he argues, to draw chatty Italian audiences back into the film. He discusses his concept of ‘vernacular cinema’ and relates it to Fulci’s picture specifically. - ‘Hell is Already In Us’ (20:30). In a new video essay, Kat Ellinger discusses Fulci’s career and, in particular, the claims that Fulci’s cinema is misogynistic. There are some broad assertions (that ‘the nature of horror’ is ‘to confront the taboo’, for example), but the premise is logical. - ‘Lucio Fulci Remembers’: Part One (20:13) and Part Two (13:12). This comprises the audio recordings Fulci produced in response to questions from journalist Gaetano Mistretta in 1988. Transcripted passages from this interview were published in Mistretta’s book Spaghetti Nightmares. Fulci reflects on his journey to becoming a filmmaker and discusses his work and its themes in detail, offering some interesting and entertaining anecdotes about his career and encounters with other filmmakers. The interview is audio only, in Italian with optional English subtitles. - Interviews: o Florinda Bolkan (28:20). Bolkan discusses her work with Fulci. She describes him as ‘a devil’ who was ‘very peculiar’: ‘And I think that’s how horror directors are supposed to be’, she adds. Her comments are in Italian, with optional English subtitles. o Sergio d’Offizi (46:21). The cinematographer reflects on his working relationship with Fulci, which began with their collaboration on Nonostante le apparenze... e purchè la nazione non lo sappia... all'onorevole piacciono le donne (The Senator Likes Women/The Eroticist, 1971) and continued with … Duckling. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. o Bruno Micheli (25:38). The film’s editor talks about his career and his collaboration with Fulci. Again, the interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. o Maurizio Trani (16:03). Make-up artist Trani discusses his work on the picture. This interview is also in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

Overall

Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling is a superb example of the thrilling all’italiana, the rural setting offering a different experience to the cosmopolitan Italian-style thrillers of the likes of Dario Argento and Sergio Martino. Fulci examines the tension between urban and rural, between rationalism and superstition, between progress and repression, in a manner that is complex but never didactic: all sides are depicted cynically by Fulci. As fans of Fulci will know, the picture is to some extent lumbered with a bizarre English language title: the Italian equivalent, ‘Non si sevizia un paperino’, translates more directly as ‘Don’t Torture Donald Duck’ - in Italy, Donald Duck is known as Paolino Paperino - and is a reference to a Donald Duck doll found at one of the murder scenes, which becomes a key clue in the solving of the crimes. Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling is a superb example of the thrilling all’italiana, the rural setting offering a different experience to the cosmopolitan Italian-style thrillers of the likes of Dario Argento and Sergio Martino. Fulci examines the tension between urban and rural, between rationalism and superstition, between progress and repression, in a manner that is complex but never didactic: all sides are depicted cynically by Fulci. As fans of Fulci will know, the picture is to some extent lumbered with a bizarre English language title: the Italian equivalent, ‘Non si sevizia un paperino’, translates more directly as ‘Don’t Torture Donald Duck’ - in Italy, Donald Duck is known as Paolino Paperino - and is a reference to a Donald Duck doll found at one of the murder scenes, which becomes a key clue in the solving of the crimes.

The film is also beautifully shot, the photography making excellent use of canted angles and selective focus. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a very pleasing presentation of the film that easily eclipses the picture’s previous DVD release. Some minor damage is present, but overall the presentation is very good, and the disc also offers the viewer a choice of the Italian track or the English dub. The former is preferable and more nuanced, but the inclusion of both is to be praised. The main feature is also supported by some very good contextual materials. Troy Howarth’s commentary is enthusiastic and thorough, and the interview with Koven also offers strong contextualisation of the main feature. The most significant material, however, comes in the form of interviews with some of the film’s key members of the cast and crew; these are thorough, detailed interviews filled with information about Fulci’s working methods and the production of this specific film. In sum, this is an excellent release and represents an essential purchase for fans of Italian thrillers. References: Karola, 2003: ‘Italian Cinema Goes to the Drive-In: The Intercultural Horrors of Mario Bava’. In: Don Rhodes, Gary (ed), 2003: Horror at the Drive-In: Essays in Popular Americana. London: McFarland & Company, Inc: 211-40 Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland Visual Comparison with Anchor Bay DVD Anchor Bay DVD

Arrow Blu-ray

Anchor Bay DVD

Arrow Blu-ray

Anchor Bay DVD

Arrow Blu-ray

Anchor Bay DVD

Arrow Blu-ray

Anchor Bay DVD

Arrow Blu-ray

|

|||||

|